Contributed by Sheryl Harry, PVN Patient Partner.

This article was originally posted by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Sheryl and CFHI have generously permitted us to re-post her story. Sheryl’s pledge is to advocate for better understanding of and care for residential school survivors, and other survivors of trauma, in long term care.

My dad, Duncan Harry, was from Ts’kw’ay’laxw First Nation in Pavilion BC.

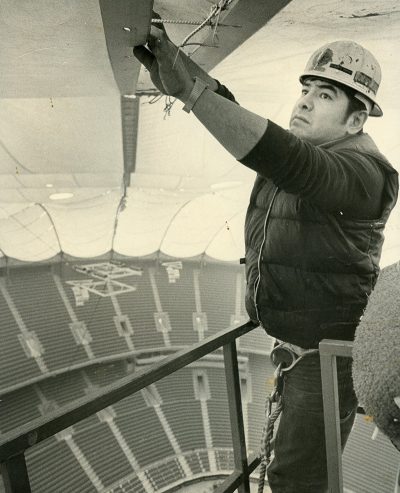

He was a skilled and proud ironworker—a foreman—who was well-liked and respected by his coworkers and bosses. In 1976, he suffered a workplace injury, falling 20 feet and landing on a concrete slab. Despite his accident, he continued to work until the injuries forced him to stop fourteen years later.

In 2011, Dad was officially diagnosed with dementia.

He was first hospitalized in April 2015 because of a badly ulcerated, severely infected leg. His leg was amputated above the knee, one month later. He remained in hospital until mid-November of that same year. On December 2, 2015, he passed away in hospice.

Throughout Dad’s hospital stay, I would stop after work and stay with him until he fell asleep. I quickly found that the dementia caused him to believe that he was back in residential school. My dad had attended both St. Joseph’s Residential School in Williams Lake, BC and Kamloops Indian Residential School in Kamloops, BC.

When I’d arrive at the hospital, I often found him shaking, teary and sometimes crying. He would ask me how they let me in. He would tell me that he didn’t talk all day because he didn’t want to get into trouble. My mom and I did our best to reorient him each day, and to let the care aides, nurses and doctors know that this was what he was experiencing. We had to repeat this “orientation” each time he was moved to a different ward (which was frequently).

Each time Dad was moved, we found it was extremely difficult to convince staff that what they thought was agitation and aggressive behaviour was actually night terrors and a response to his perceived environment – to Dad thinking he was back in residential school. Mom and I asked repeatedly that staff call us to be with Dad anytime (day or night). We both live and work within five minutes of the hospital. This never happened. Instead, staff continued to call security, use restraints and inject him with antipsychotic medications when he became agitated or aggressive. This was not making things better for him. It made it much worse.

I was extremely protective of my dad during his time in hospital, the Tertiary Palliative Care Unit (TPCU) and hospice. Mom and I made sure to assist every time the nurses washed and re-positioned Dad, as it was very frightening for him. The last word he ever said was “No!” when the nurses were washing him.

When my mom and grandma wanted Dad to have the last rites, I was very concerned that having a priest standing by his bed would really scare him. I talked to one of the nurses about the possibility of finding a priest who would come in regular clothing and whisper the last rites while Dad was sleeping. The nurse was very understanding – but unfortunately, he advised that the one priest he was able to reach was unwilling to accommodate our request. Thankfully for Dad and our family, he recommended the Hospice Spiritual Coordinator, who was lovely.

After Dad passed away, I started seeing a grief counsellor. Eventually, I started volunteering and took a hospice volunteer education program. They have put me in touch with one of the nurses from TPCU, who advised that they had begun doing things differently since my dad’s time with them. At the time Dad was there, staff were not aware of the effects of residential schools on survivors. I was told that this has since started to change.

I feel great concern about Dad’s fellow residential school survivors. Some may have dementia. Some likely experience post-traumatic stress. Some will end up in hospital. I worry that these survivors will experience – or are experiencing – the same things that Dad did. Many survivors would now be around Dad’s age when he was diagnosed.

I believe there is an urgent need to educate healthcare workers (as well as survivors and families) about what happens when residential school survivors, post-traumatic stress, dementia and hospitals collide and the most effective ways of helping, communicating with and supporting survivors and families.

I don’t believe survivors should be re-traumatized in hospital. Families shouldn’t feel they need to be with their loved ones in hospital 24 hours a day to protect them from further trauma. They should be there because they choose to be. Because they are partners in care. Because they are helping to provide patient-centred care.

The elder years are a time that should be respected and honoured. I really did my best to honour Dad’s journey throughout his time in hospital, TPCU and hospice. He loved to help people and I am positive he would really want to help his fellow Residential School Survivors and anyone with post-traumatic stress.

I feel like my Dad and I share the same soul, or the same kind of soul. In my first year of grieving, I was tortured, wondering why he had to suffer so much during his life. I am still trying to understand this, but I think I’m here to do something about his suffering, even though he’s across with our ancestors now.

I have signed up to volunteer with the Patient Voices Network. In September of this year, I attended the Better Together Policy Roundtable as one of CFHI’s Patient Advisors. I want to bring a voice to this issue. I hope you will as well.

Note: The information and material here may trigger unpleasant feelings or thoughts of past abuse.

If you’re experiencing emotional distress and want to talk, call the 24 Hour Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419 or the First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line 1-855-242-3310.